If Conservatives care about the ministerial code, at least 11 cabinet members should resign

Boris Johnson (prime minister)

Section 1.3.c of the ministerial code

“It is of paramount importance that Ministers give accurate and truthful information to Parliament, correcting any inadvertent error at the earliest opportunity.”

Johnson has repeatedly lied in the House since becoming prime minister. For this particular case, we shall use this example from Byline Times:

29 January 2020: Boris Johnson said at prime minister’s questions, “The SNP has not had a debate in its parliament on education for two years”.

Since 29 January 2018, there have been six debates on motions about schools, two members’ business debates, and four statements by ministers followed by questions.

The fact-checking organisation, Full Fact, contacted Downing Street to ask for clarification, but did not receive a response.

Rishi Sunak (chancellor of the exchequer)

In November, the government ethics watchdog was asked to investigate Sunak for breaking the ministerial code. The violation in question involved not declaring his wife’s portfolio in the ministerial register. This is not a confirmed violation of the code, but there are plenty of other examples we can use.

Section 1.3.h of the ministerial code

“Ministers in the House of Commons must keep separate their roles as Minister and constituency Member.”

However, as Jane Thomas, Andy Brown and Stella Perrott have written for Yorkshire Bylines, Sunak has been brazenly playing pork-barrel politics with the levelling-up fund. The algorithm devised by Sunak has put his own wealthy constituency of Richmond as a top-priority seat, as opposed to places like Barnsley and Sheffield, which have much higher poverty rates.

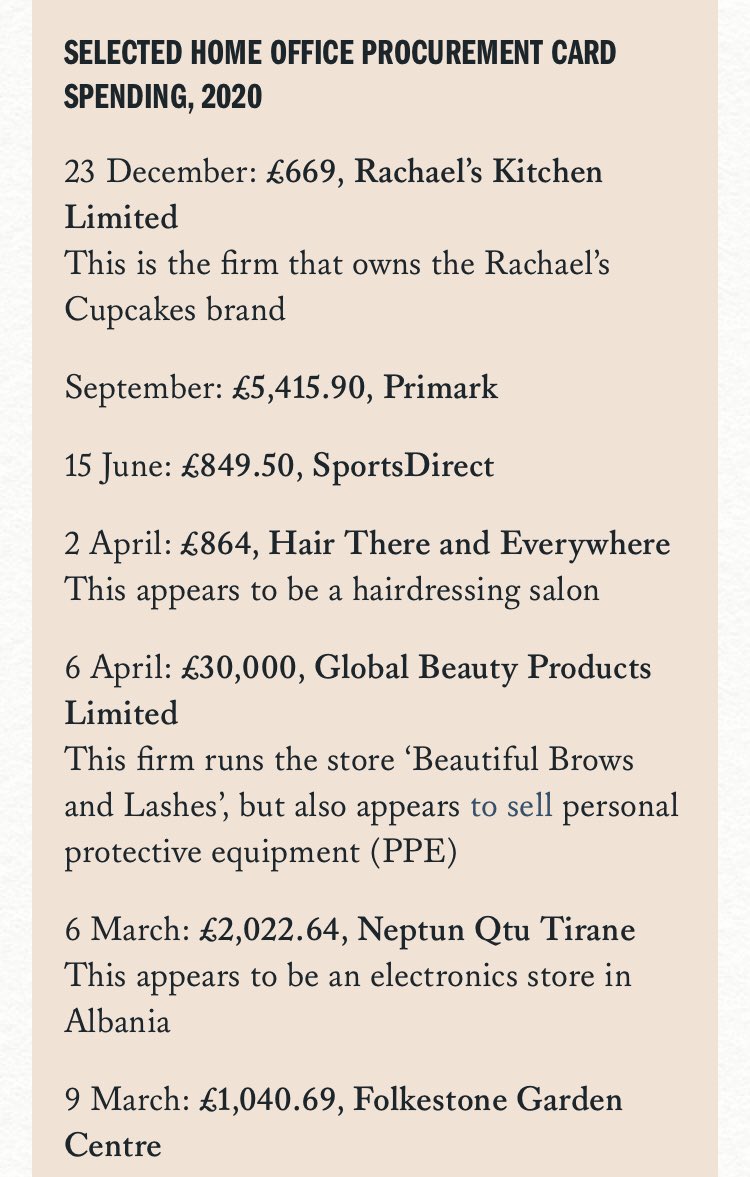

Priti Patel (home secretary)

Section 1.2 of the ministerial code

“Harassing, bullying or other inappropriate or discriminating behaviour wherever it takes place is not consistent with the Ministerial Code and will not be tolerated.”

Accounts of Patel’s bullying are an open secret in Westminster. After the resignation of Sir Philip Rutnam, an inquiry into Patel revealed that she had broken the ministerial code, although it has not yet been published.

Michael Gove (chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster)

Section 1.3.d of the ministerial code

“Ministers should be as open as possible with Parliament and the public, refusing to provide information only when disclosure would not be in the public interest, which should be decided in accordance with the relevant statutes and the Freedom of Information Act 2000.”

However, Gove has been running a secretive ‘clearing house’ operation within the Cabinet Office, attempting to suppress freedom of information requests wherever possible. This clearing house has tried to avoid releasing information about events such as the contamination of NHS blood banks with HIV-positive samples. Gove is hardly being as open as possible.

Matt Hancock (secretary of state for health and social care)

Hancock has broken the ministerial code several times, particularly during the coronavirus pandemic. For this we shall stick to our good friend section 1.3.c on honesty, citing this example of dishonesty from Byline Times

On 2 November 2020, Hancock said in the House of Commons, “In April, on schedule, we delivered the target of 100,000 tests a day”.

This figure is misleading.

According to Full Fact, “of the 122,347 tests that the Government has said were completed on April 30, 27,497 are home tests and 12,872 were sent out to satellite sites. This suggests that just 81,978 of the tests were actually processed”.

Robert Jenrick (secretary of state for housing, communities, and local government)

Section 1.3.f comes up again for Robert Jenrick.

“Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or appears to arise, between their public duties and their private interests”.

In June 2020, Jenrick granted planning permission for a £1bn property development by Conservative donor Richard Desmond. In overruling a local planning inspector, Jenrick saved Desmond £40m, which he would have had to pay in community levies, which are used to improve local infrastructure.

Jenrick helped a Conservative donor avoid paying tax that would have gone directly to local communities. This is a clear case of conflict of interests.

Alister Jack (secretary of state for Scotland)

Section 1.3.i of the ministerial code

“Ministers must not use government resources for Party political purposes”.

However, Alister Jack used the gov.uk website to promote a Daily Mail article he’d written. The article both praised Douglass Ross, and criticised the SNP government, and was thus blatantly party political.

These ministers broke the ministerial code during previous administrations

Dominic Raab (foreign secretary)

As Theresa May’s Brexit secretary in 2018, Raab refused to give evidence to parliament on Brexit negotiations. This broke the ministerial code, which requires transparency to parliament on such matters.

Grant Shapps (secretary of state for transport)

In 2015, it was revealed that Shapps had been employed under a fake name as a web designer. This falls foul of several aspects of the ministerial code, both failing to disclose his full set of interests, and coming under suspicion of conflict of interest due to this obstruction.

Gavin Williamson (secretary of state for education)

When secretary of state for defence, Gavin Williamson allegedly broke the ministerial code in leaking details of Huawei in the UK’s 5G infrastructure.

Liz Truss (secretary of state for international trade)

Section 1.3 of the ministerial code

“The Ministerial Code should be read against the background of the overarching duty on Ministers to comply with the law and to protect the integrity of public life”.

Back in 2019, Truss approved a shipment of arms to Saudi Arabia, which could be used in the war in Yemen. The shipment breached an order by the Court of Appeals, and Truss admitted that she had acted unlawfully.